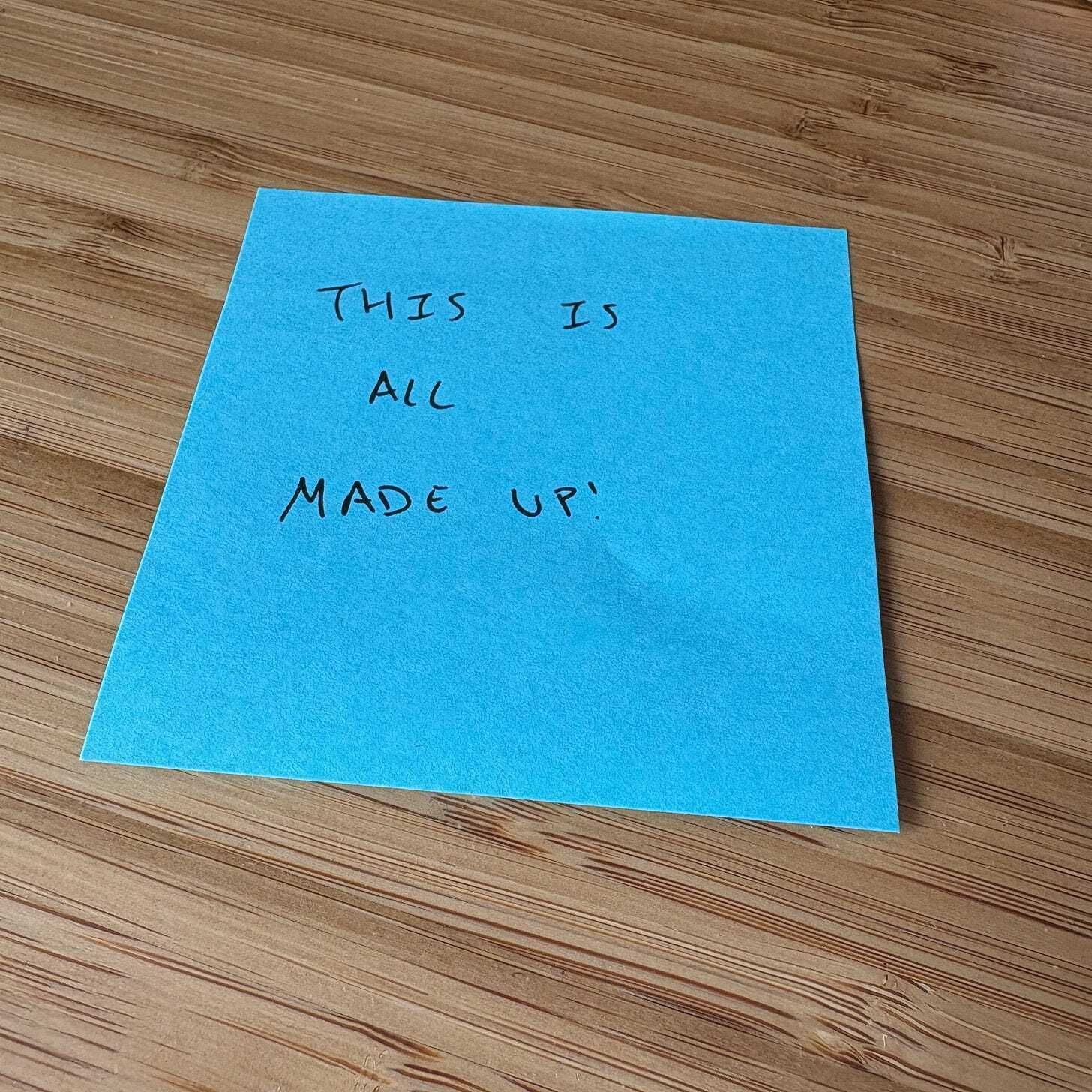

This is all made up.

It’s written on a post-it note stuck to my desk, just under my monitor. I look at it all the time. I also have it as a stickie on my Mac, so when I’m out and about, I still get a glimpse of this strange, comforting little mantra.

This is all made up.

What does that mean to me?

Mostly, it reminds me not to worry so much about what other people think. That’s the biggest gift it gives me. It’s a reminder that we live in a world made up of rules created by other people. Products designed by other people. Buildings built by other people. Laws written by other people. It’s all basically made up.

That doesn’t mean it’s not real. But it means we made this. I’m part of that too. So I can make things up too. I can follow my own dreams. They matter. They’re worth pursuing.

That’s one of the hardest truths I’ve had to work to accept: that my dreams matter. That I matter. And that I’m allowed to believe that.

I love mantras. I love affirmations. But here’s the catch — sometimes affirmations backfire. There’s research on this too. If you say something you don’t actually believe, your brain might push back against it. It can go from inspiring to damaging. It’ll think, “That’s not true,” and shut down to anything else you try to say.

That happens to me with statements like “I am successful.” Because when I say that, my brain immediately pulls out a checklist of all the ways I’m not. I’m not financially independent. I don’t have a million subscribers. I don’t have brand deals. I haven’t written a bestselling book. I’m not famous. I don’t know famous people. I haven’t made it.

So my brain asks, “How exactly are you calling yourself successful?” And then it spirals.

It gets mean.

Really mean.

It starts in on how I’ve spent years working on this, and I still haven’t achieved those external markers of success. It asks, “Why are you still trying?” It whispers that I should just quit. Not just quit the goal. Quit the whole thing. Quit everything. It says, “Just give up. Who even cares?”

It’s wild how cruel we can be to ourselves.

And I ask myself all the time — why are we like this? Why do we offer our friends so much love, support, and compassion, and yet starve ourselves of the same?

If a friend told me they didn’t feel successful, I’d never tell them they weren’t just because they weren’t rich or famous. I’d remind them of the joy they bring people. I’d talk about their health, their kindness, their resilience, their family, their courage, their growth. I’d help them see how much they have to be proud of.

Then I’d turn around and tear myself down.

I’m so tired of that cycle.

I have done a lot. I do have things to be proud of. I’m grateful for so many things. I have, at the time of writing this, nearly 40 subscribers to this newsletter. That’s 40 people who care enough to read what I write. That’s a lot. And even better — I get kind notes from many of you, saying these words helped you in some way. That means the world to me. It makes all of this worth it.

And still, I have days when I feel like a failure.

So what is it? Is it fear?

Am I just afraid that if I give it my all, I’ll come up short? That if I try too hard and still don’t reach the dream, it’ll hurt worse than if I had never tried at all? That’s what it feels like sometimes. It’s as if my brain fast-forwards, imagines the worst outcome, and decides it’s best to protect me from it. It tells me to quit now. It says quitting early will hurt less than failing later.

Maybe that’s fear’s job — to bring the imagined pain of a future scenario into the present moment. It’s worst-case scenario thinking. And I’m tired of it.

I appreciate that my brain is trying to protect me, but the system it’s running is outdated. It’s using ancient fear logic, the kind meant to save us from predators. Fear is binary. It’s either off, or it’s on. Relaxed, or fight-or-flight. There’s no in-between.

So when I imagine failing at my dream, my brain interprets it as danger. It treats writing an essay and clicking “publish” as if I’m walking into a bear’s den. It flips the fear switch and goes, “He’s going to die.”

But I’m not. I’m literally just sitting here, pressing buttons.

I’m not stepping into traffic. I’m not trying to pet a lion. I’m not swimming with sharks. I’m pressing buttons in a coffee shop on a rainy day. And my brain is sounding the alarm anyway.

Well, guess what, brain. I’m fine.

And here’s what I’ve been trying to do lately — hijack that system. I’ve been practicing best-case scenario thinking.

Because if worst-case scenarios are made up, best-case scenarios are too. And they’re just as valid. Everything is imagination until it becomes reality.

So I imagine what would happen if I just kept going.

What if I kept writing this newsletter, and it slowly grew? What if one day someone reads a post and reaches out to ask if I’ve ever considered writing a book? What if they work for a publisher? What if I write it? What if it connects with people? What if it becomes a bestseller? What if I end up on talk shows? What if I gain thousands or even millions of followers? What if I get to do what I love, full-time, every day?

My heart races — in a good way.

This version of the future feels so alive, I can almost believe it’s already happened. And that belief motivates me. It fuels me to keep writing, keep sharing, keep building, keep dreaming.

And guess what? In that version of the story, I am so much happier.

I want to spend more time with that version of my brain — the one that’s open and curious and optimistic. That part of me is hopeful, not just for my own future, but for everyone’s. I want all of us to feel safe, supported, and excited to wake up in the morning. That’s my real dream. A better world, built by people who believe we can create something beautiful together.

Because — like I said at the start — this is all made up.

So why not imagine something incredible? Why not visualize a version of the future that feels fulfilling? Why not let those feelings settle into our bodies now, so we’re ready to spot opportunities when they show up?

I’ll leave you with a study from the world of positive psychology. It’s one of my favorites.

Researchers brought together two groups of people. One group identified as “lucky.” The other, “unlucky.” Each person was handed a newspaper and told to count how many photos were inside. Once they had the number, they were to report back.

The “unlucky” group took an average of two minutes to complete the task.

The “lucky” group? A few seconds.

Why?

Because on the front page of the newspaper, in big bold letters, was a sentence: “There are 43 photos in this newspaper.” A second line in the middle of the newspaper said, “Tell the researcher you’ve found the answer.”

It was right there, and most of the “unlucky” people missed it.

Why? Because when we expect things to be hard, or when we’re operating from fear or skepticism, we stop seeing what’s right in front of us. Our brain filters it out. They focused on the task of counting the photos, without a thought that there could be a shortcut out of it.

Our brain’s visual system isn’t only a mechanical system of lenses — our brains hold a lot of power about what we “see” and what we “don’t see”! Things right in front of us, just like in this example, can literally go unnoticed.

On the flip side, people who are optimistic — or “lucky” — tend to see more. They stay open. Their brains are scanning for good news, so they notice it when it shows up. Then they act on it.

That’s what I want for me. And for you. And for all of us.

Because this is all made up.

So let’s make up something wonderful.

If this hit home for you, I’d love to hear it. Drop a comment or send it to someone else whose brain is also a little mean sometimes.